|

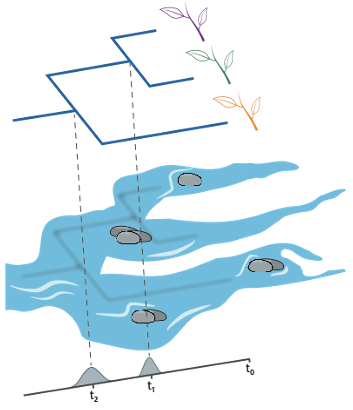

Impact of drainage basin formation on the evolution of aquatic plants in Neotropical rivers The dynamic landscape of northern South America holds and incredibly diverse flora. My research provides a novel perspective on the role of Andean uplift and subsequent drainage basin formation on the evolutionary trajectory of plants distributed across the Andes, by shifting the focus from terrestrial to aquatic plants. In the past, I investigated how populations of aquatic plants in the genus Marathrum (Podostemaceae) are genetically structured, how they are related to one another, and when they diverged. This work was published in the New Phytologist and was highlighted by the media. This work incorporated genomic datasets (genome-skimming, target enrichment, and ddRADseq) and phylogenomic, phylogenetic networks, population structure and divergence dating analyses. |

Marathrum is the only plant group restricted to rivers and distributed across the Andes in northern South America. Left: Marathrum foeniculaceum (highly dissected leaves). Right: Marathrum utile (entire leaves). I found evidence suggesting that when these two species co-exist, they hybridize. Hybrids show the phenotype of M. foeniculaceum.

|

|

Botany and Geogenomics

Past studies in plant evolution have shed light on how the geological history of our planet shaped plant evolution by establishing well-known patterns (e.g., how mountain uplift resulted in high rates of diversification and replicate radiations in montane plant taxa). Under this approach, information is transferred from geology to botany, by interpreting data in light of geological processes. I advocate for a conceptual shift in this traditional approach to specifically transfer information from botany to geology. This conceptual shift follows the goals of the emerging field of geogenomics and emphasizes that plant systematics can go beyond investigating patterns in light of landscape change, to reduce the inherent uncertainty in models of paleotopography, river system structure, and land connections through time. In my past research, I have integrated phylogenomics, population genetics, and phylogenetic network analyses to reconstruct the timing and pattern of drainage basin formation across the Andes in northern South America. A preprint where I lay out current challenges that are specific to analytical approaches for plant geogenomics in available here. I describe the scale at which various geological questions can be addressed from biological data, and what makes some groups of plants excellent model systems for geogenomics research. |

|

Comparative diversification of Neotropical plants in aquatic habitats shaped by Andean uplift I aim to determine the generalities and idiosyncrasies of the role of Andean uplift on the evolution on the Neotropical aquatic flora (plants in rivers and wetlands). I am using ddRADseq data to establish when populations and species of Ludwigia (Onagraceae) distributed across the Andes in northern South America diverged from one another. Future work in this research area include investigating phylogeographic patterns and the contributions to diversification of biotic characteristics using state-dependent speciation and extinction models across multiple focal groups of plants in wetlands and rivers. |

|

Biotic and abiotic drivers of Andean plant diversification

As a postdoc in the Lagomarsino Lab at LSU, I am investigating thecomplexity of species diversification processes in the tropical Andes, the World’s most species-rich biodiversity hots. I am part of a team of researchers conducting fieldwork, developing, and implementing novel state-dependent diversification models to jointly infer the roles of long-distance dispersal, movement along elevational gradients, and trait evolution in lineage diversification. This project includes comparative studies across multiple clades that share Andean occurrence, but differ in environmental preferences, morphology, and ecological interactions. |

|

|

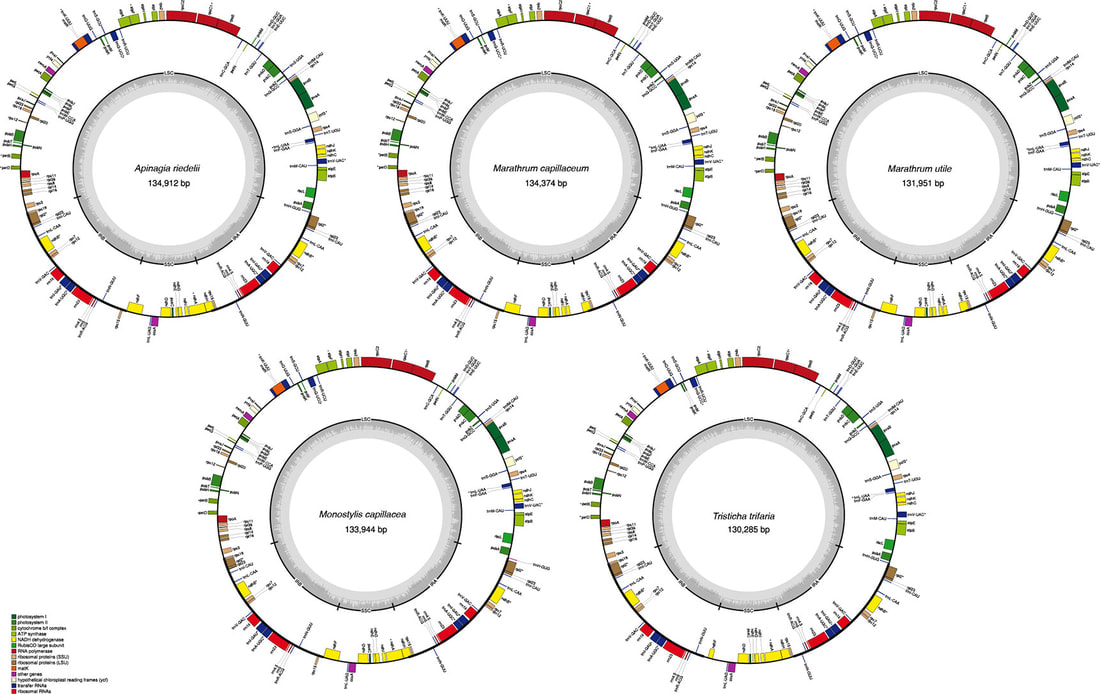

Plastid genomes of riverweeds (Podostemaceae)

Together with the Hydrostachyaceae, the Podostemaceae are the only plant family that live attached to rocks in fast-flowing aquatic ecosystems. My collaborators and I assembled full plastomes for 5 species of riverweeds using genome-skimming data to determine the structure, gene content, and rearrangements in the plastid genomes of the family. The Podostemaceae have one of the smallest plastid genomes reported so far for the Malpighiales, possibly due to variation in length of inverted repeat (IR) regions, gene loss, and intergenic region variation. The uncommon loss or pseudogenization of ycf1 and ycf2 in angiosperms and in land plants in general is also found to be characteristic of Podostemaceae (Bedoya et al., 2019. Frontiers in Plant Science. |

|

Comparative plant anatomy

I am passionate about plant anatomy in a comparative framework. In this field, the questions that interest me the most are how distantly related groups evolved to live in the same environments and how the mechanisms used to adapt to special conditions differ or are similar among closely related groups (Bedoya et al., 2015). Aquatic plants are a great model system to tackle these questions as the aquatic habit evolved multiple times across angiosperms. |

|

|

Documenting plant diversity and conservation of plants in rivers

Traveling to remote areas, collecting and identifying plants, learning from locals, and getting my feet wet has been the experience of my life. I am committed to expanding representations of aquatic plants in herbaria. Alongside three colleagues, I produced a book with 291 species of aquatic plants from the Orinoco basin of Colombia. Aquatic plants in Colombia are understudied, but their ecological importance in aquatic ecosystems is invaluable. Multiple collections are new records for the region and even the country, and all are publicly available.The book is dedicated to the inhabitants of the Orinoco basin of my beautiful home country. My collections of Marathrum account for more than half go the historical records of the genus since is was first collected in Colombia in 1801 (Bedoya & Olmstead 2022). My past research has shown that the future of rivers and of riverweeds is linked. I am developing my research in riverweeds as a powerful too for conservation of Neotropical rivers. |

|